Isabel Tejeda, curator of the project

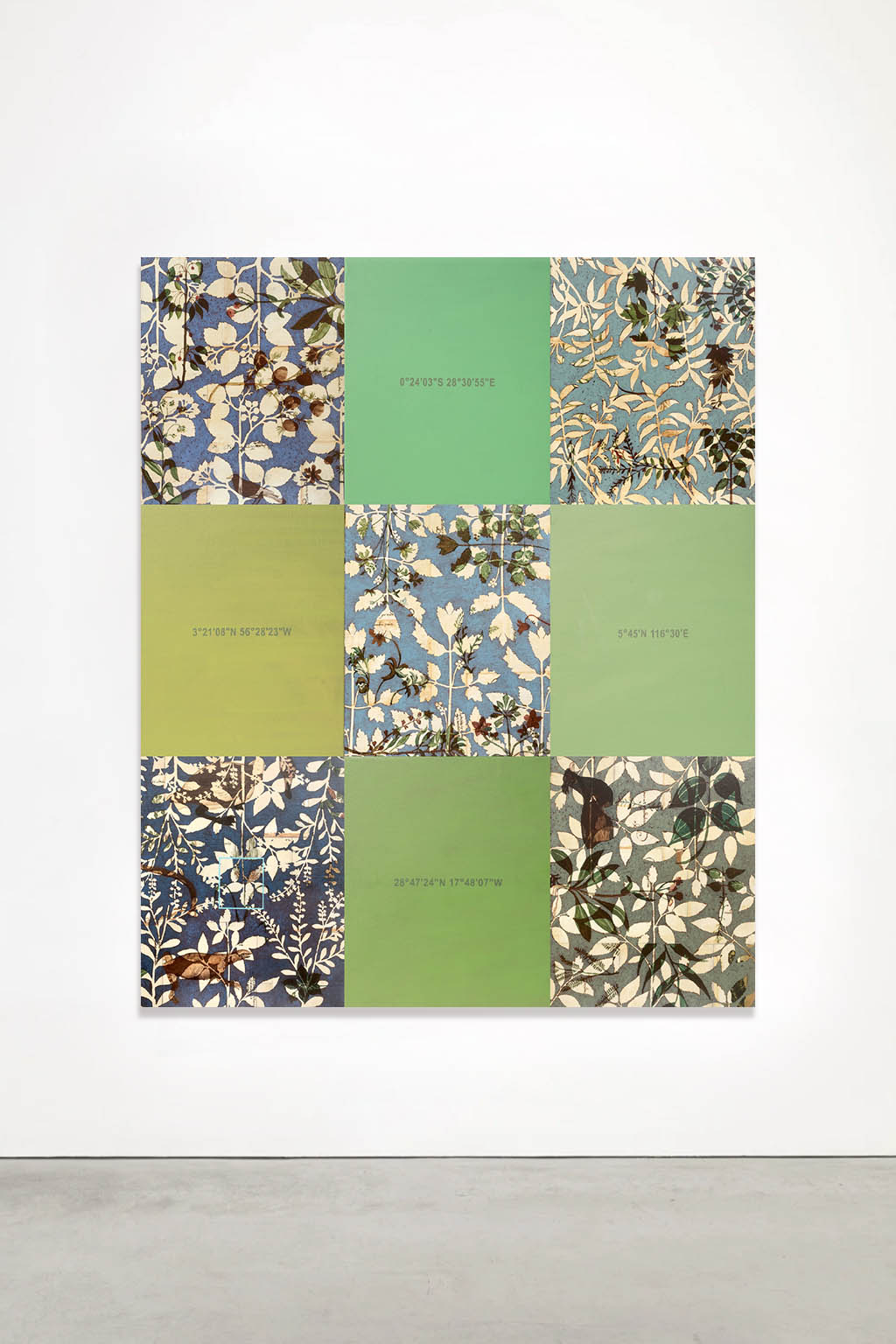

The expedition Nomadic Station invites reflection on two key ideas: the act of seeing in constant motion, and the mechanisms invented to classify and compile the world. When one ventures out to meet things—not to dominate, subdue, or control them, but with the intention of listening, learning, and understanding—it no longer seems necessary to establish a hermetic or closed system of appropriation. Rather, it becomes more appropriate to cultivate an ars combinatoria between what is found and what is kept, in order to provoke a disruptive gaze—a fluctuating gaze that questions how we “inhabit” the natural environment.

This project, curated by Isabel Tejeda, presents paintings, audiovisual works, and collected stones. Each exhibition room unfolds the narrative thread through the following questions: Who has had the power to observe and contemplate the world? What does it mean to think and paint from a Nomadic Station? Is it a real or imagined place that holds the uncertainty of the observer? Why do we feel the need to create patterns to classify and domesticate what we call “nature”?

The stories of female explorers—especially those who kept travel diaries or field notebooks—are rare. Yet some defied the conventions of their time by funding their own journeys and even dressing as men to join scientific expeditions. This was the case of Jeanne Baret, lover of the naturalist Philibert Commerson, who disguised herself aboard the ship Étoile, captained by the Comte de Bougainville, becoming the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.

An audiovisual collage presents early twentieth-century footage of expeditions to Antarctica, capturing heroic, exploratory action. In contrast, other works reference the practices of naturalists like Anna Atkins, Maria Sibylla Merian, and geologist Florence Bascom, as well as literary approaches to nature by women such as Emily Dickinson, Clarice Lispector, and María Zambrano.

Observing nature has meant, for our species, not only developing the capacity to name and record its forms, but also to impose boundaries—tracing lines between the organic and the inorganic, the natural and the artificial. Over the centuries, we have created discourses that distance us from what we perceive, as if we were separate from the very nature we seek to understand. The Comte de Buffon, director of the first Natural History Museum, once expressed it this way: “The discourse of nature is nothing but nature transformed into discourse.” Thus arose taxonomies and nomenclatures, archives and their classifications, catalogues and drawn boundaries.

Why collect every stone, every plant,

again and again?

Isabel Tejeda, curator of the project

The expedition Nomadic Station invites reflection on two key ideas: the act of seeing in constant motion, and the mechanisms invented to classify and compile the world. When one ventures out to meet things—not to dominate, subdue, or control them, but with the intention of listening, learning, and understanding—it no longer seems necessary to establish a hermetic or closed system of appropriation. Rather, it becomes more appropriate to cultivate an ars combinatoria between what is found and what is kept, in order to provoke a disruptive gaze—a fluctuating gaze that questions how we “inhabit” the natural environment.

This project, curated by Isabel Tejeda, presents paintings, audiovisual works, and collected stones. Each exhibition room unfolds the narrative thread through the following questions: Who has had the power to observe and contemplate the world? What does it mean to think and paint from a Nomadic Station? Is it a real or imagined place that holds the uncertainty of the observer? Why do we feel the need to create patterns to classify and domesticate what we call “nature”?

The stories of female explorers—especially those who kept travel diaries or field notebooks—are rare. Yet some defied the conventions of their time by funding their own journeys and even dressing as men to join scientific expeditions. This was the case of Jeanne Baret, lover of the naturalist Philibert Commerson, who disguised herself aboard the ship Étoile, captained by the Comte de Bougainville, becoming the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.

An audiovisual collage presents early twentieth-century footage of expeditions to Antarctica, capturing heroic, exploratory action. In contrast, other works reference the practices of naturalists like Anna Atkins, Maria Sibylla Merian, and geologist Florence Bascom, as well as literary approaches to nature by women such as Emily Dickinson, Clarice Lispector, and María Zambrano.

Observing nature has meant, for our species, not only developing the capacity to name and record its forms, but also to impose boundaries—tracing lines between the organic and the inorganic, the natural and the artificial. Over the centuries, we have created discourses that distance us from what we perceive, as if we were separate from the very nature we seek to understand. The Comte de Buffon, director of the first Natural History Museum, once expressed it this way: “The discourse of nature is nothing but nature transformed into discourse.” Thus arose taxonomies and nomenclatures, archives and their classifications, catalogues and drawn boundaries.

Why collect every stone, every plant,

again and again?

E CA, Espai d’art contemporani

EL CASTELL

Riba-roja del Túria [Valencia]

23/10/2024 – 23/03/2025