Nomadic Station

E CA, Espai d’art contemporani

EL CASTELL

Riba-Roja del Túria [Valencia]

23/10/2024 – 23/03/2025

Painting Rocks

Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) wrote about rocks and plants. His relentless curiosity led him to “go out to meet things,” obsessed—among other topics—with the formation of volcanoes. Similarly, American geologist Florence Bascom (1862–1945), who had to study natural sciences hidden behind a curtain in the classroom, devoted herself to classifying the structures of acidic volcanic rocks. Like Humboldt, Bascom sought to unravel the processes of the Earth’s crust, especially in specific regions of Pennsylvania.

But why are we drawn to rocks—those inert elements of nature that shelter us from the elements, that we have transformed into temples, engraved with symbols, or analyzed to classify their internal structures?

According to scientific taxonomies, rocks fall into three categories: sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic. Sedimentary rocks encapsulate the passage of time. They bear traces of extinct plant and animal species and sometimes entrap objects crafted by humans.

I feel a deep curiosity for the historical uses of stones and the stories they hold. One compelling example is Stonehenge, a megalithic monument composed of 93 rocks arranged in concentric circles—a testimony to centuries of collective effort. For over 1,500 years, enormous blocks were quarried and transported, such as the sarsen stones from southern England and the bluestones from Wales. What fascinates me is that recent studies suggest the great central rock, the Altar Stone, may have originated in Scotland, 700 kilometers away—adding a new dimension to the connections between ancient communities. For Roger Caillois, rocks are “immobile matter in the longest stillness,” and he adds, “they have always been here since the beginning of the planet.”

For over 15 years, I have been collecting stones found in different places: quarries, mountains, or coastal shorelines. This seemingly trivial act of gathering propels me to explore our tendency—perhaps even a homeostatic one—to narrate stories. It always begins the same way: I’m walking, and I notice a stone that stands out. That stone suddenly “becomes” singular, capturing all my attention. I examine its conglomerated shape, the striking combination of colors in its materials, and I trace its contours with my fingers—contours revealed by the erosion of time. I also carefully assess its weight, because I rarely pick up just one. When the urge to bring them to the studio takes hold, I might carry up to 20 rocks of various sizes and shapes. I walk with them to the car; sometimes they go into a backpack or a shopping cart, but more often I carry them in the woven cradle formed by my two interlaced hands. Perhaps, later, I’ll decide to paint one.

List of the representational strategies I usually work with:

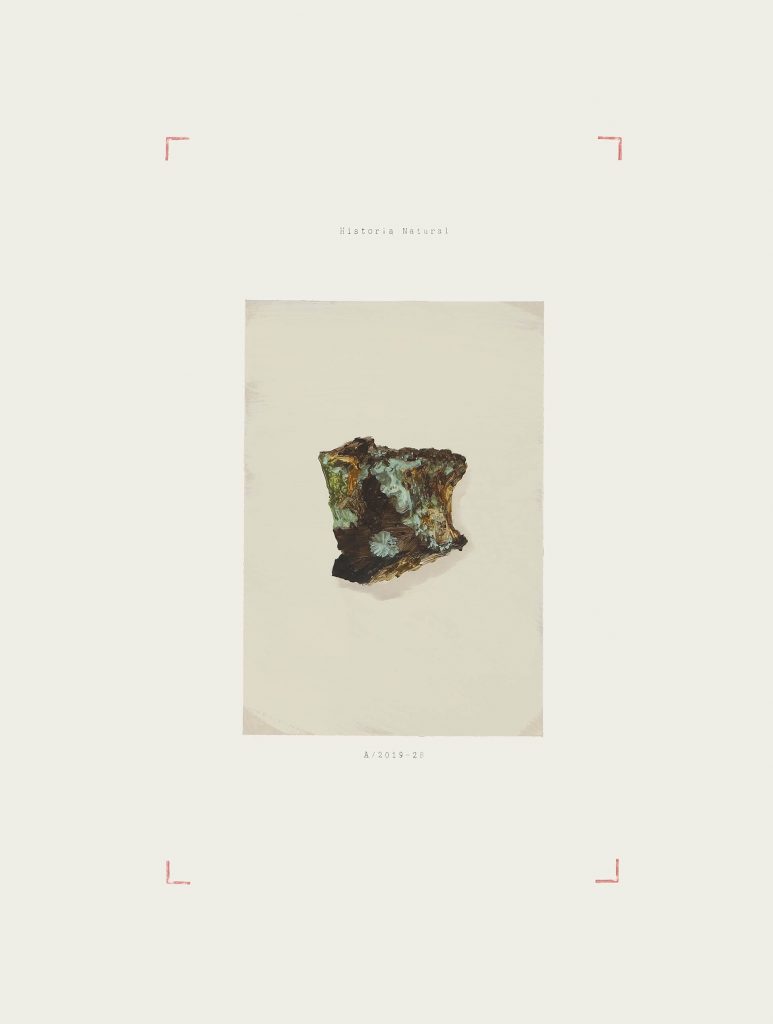

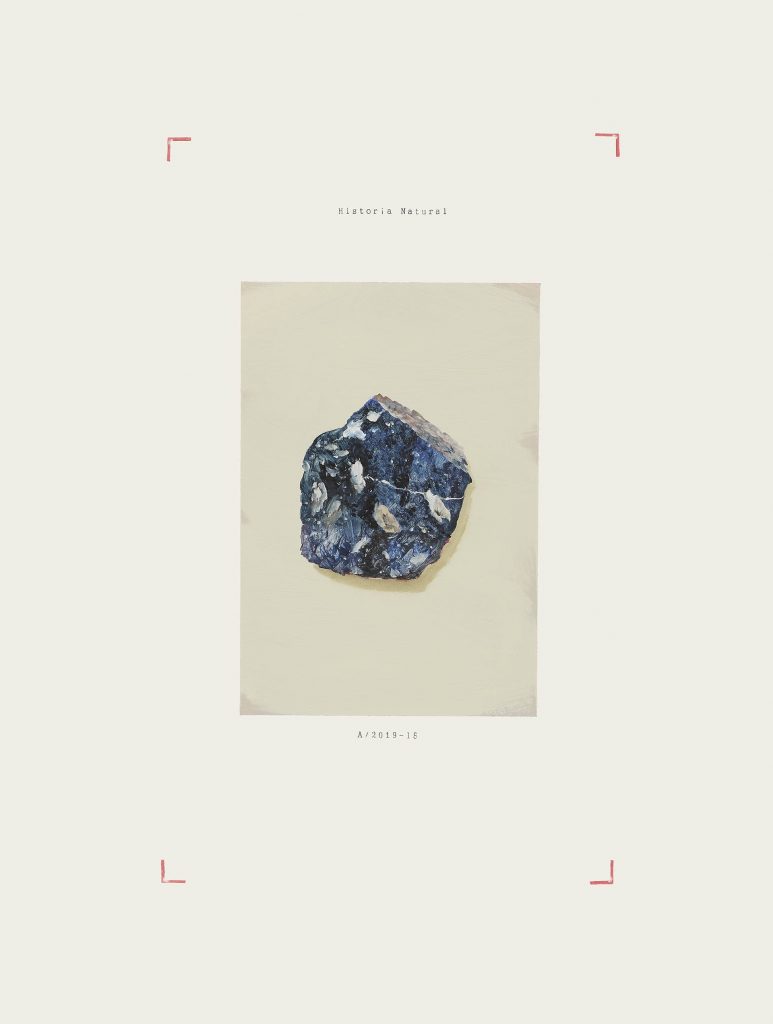

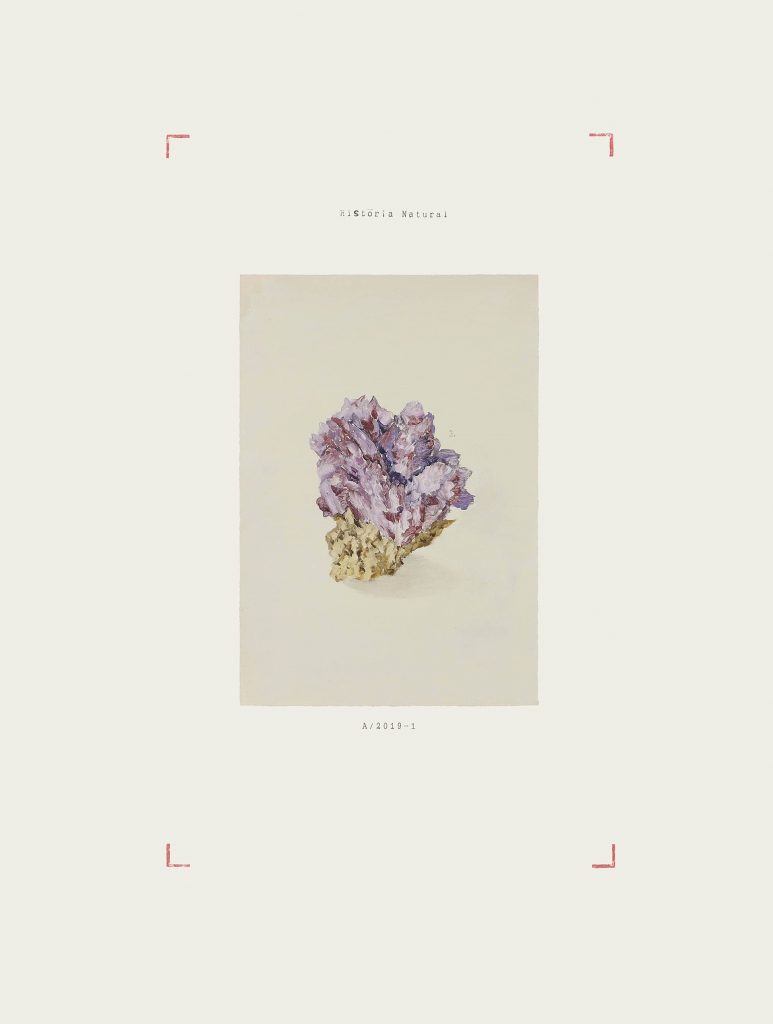

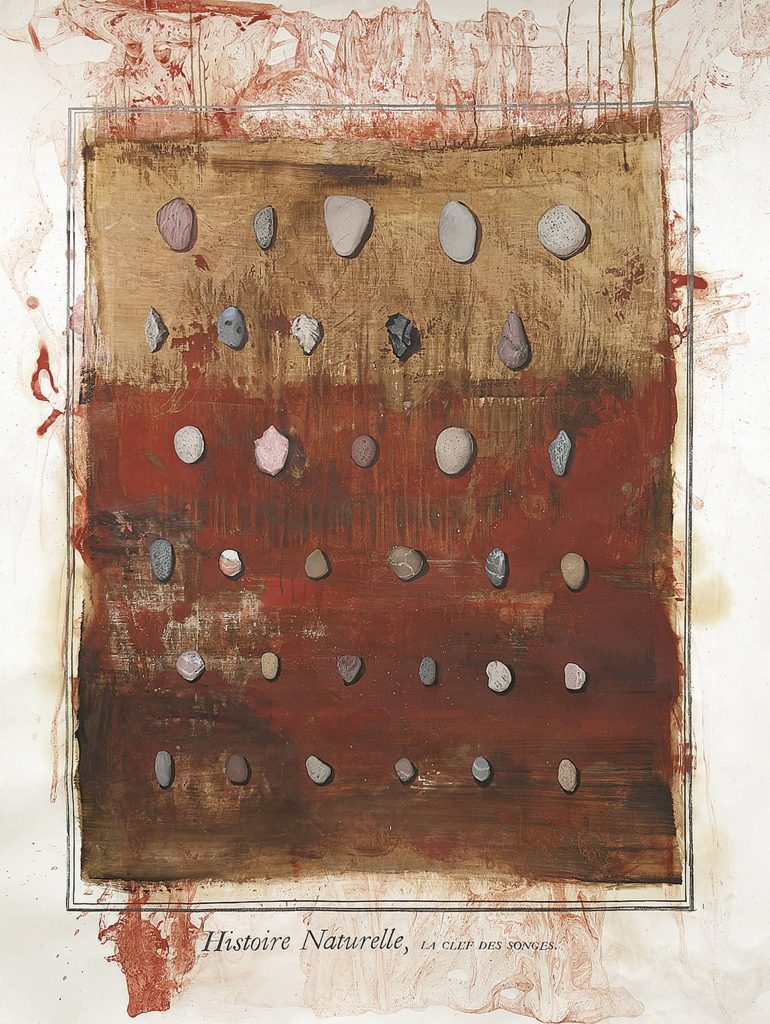

I have used the trompe-l’œil technique to depict scientific mineral collections through a quick yet precise painterly gesture, focusing on the interplay of color.

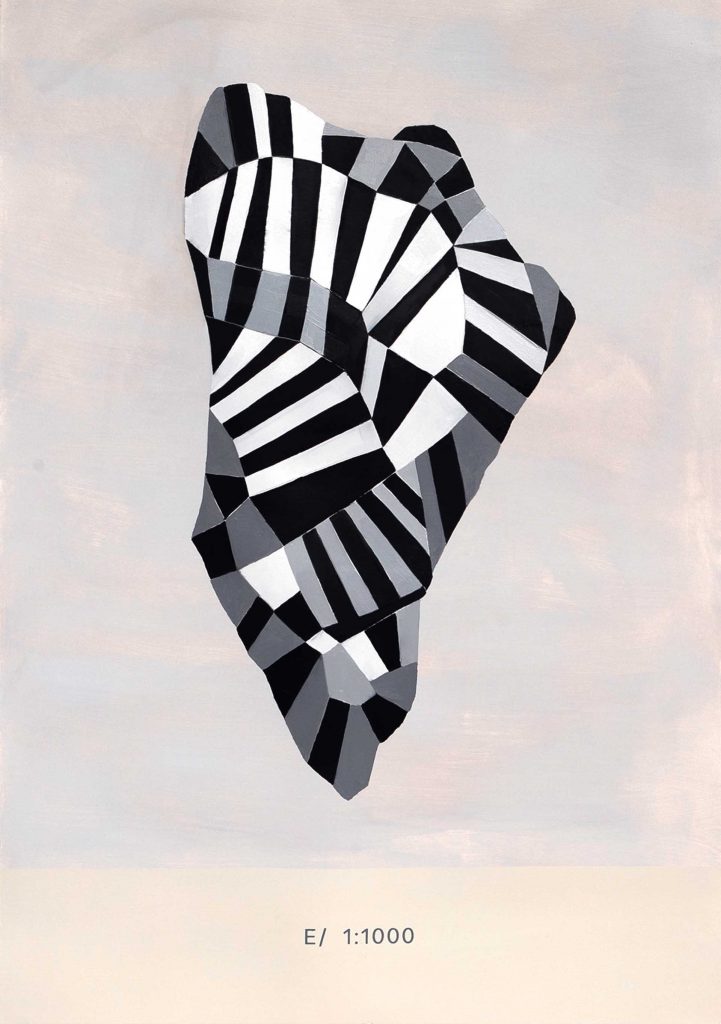

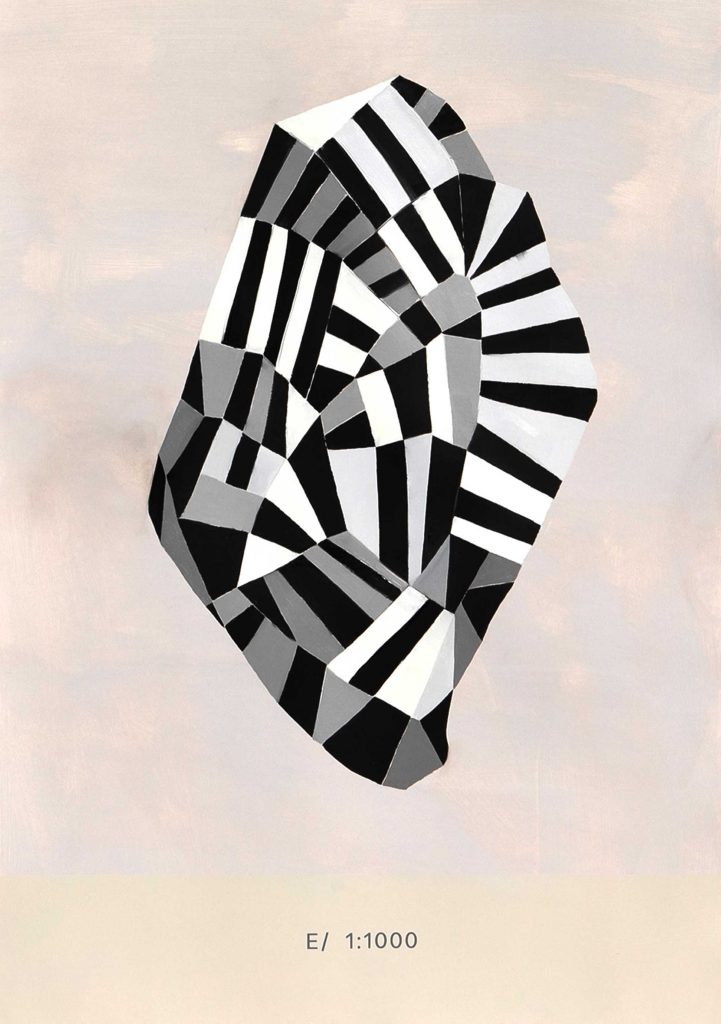

I have explored their volume using grayscale gradients that evoke digital rendering processes and the vast scale of geological time.

My most recent strategy has involved drawing the literal perimeter of each stone, in order to enclose human gestures and our compulsion to create patterns.

Painting Rocks

Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) wrote about rocks and plants. His relentless curiosity led him to “go out to meet things,” obsessed—among other topics—with the formation of volcanoes. Similarly, American geologist Florence Bascom (1862–1945), who had to study natural sciences hidden behind a curtain in the classroom, devoted herself to classifying the structures of acidic volcanic rocks. Like Humboldt, Bascom sought to unravel the processes of the Earth’s crust, especially in specific regions of Pennsylvania.

But why are we drawn to rocks—those inert elements of nature that shelter us from the elements, that we have transformed into temples, engraved with symbols, or analyzed to classify their internal structures?

According to scientific taxonomies, rocks fall into three categories: sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic. Sedimentary rocks encapsulate the passage of time. They bear traces of extinct plant and animal species and sometimes entrap objects crafted by humans.

I feel a deep curiosity for the historical uses of stones and the stories they hold. One compelling example is Stonehenge, a megalithic monument composed of 93 rocks arranged in concentric circles—a testimony to centuries of collective effort. For over 1,500 years, enormous blocks were quarried and transported, such as the sarsen stones from southern England and the bluestones from Wales. What fascinates me is that recent studies suggest the great central rock, the Altar Stone, may have originated in Scotland, 700 kilometers away—adding a new dimension to the connections between ancient communities. For Roger Caillois, rocks are “immobile matter in the longest stillness,” and he adds, “they have always been here since the beginning of the planet.”

For over 15 years, I have been collecting stones found in different places: quarries, mountains, or coastal shorelines. This seemingly trivial act of gathering propels me to explore our tendency—perhaps even a homeostatic one—to narrate stories. It always begins the same way: I’m walking, and I notice a stone that stands out. That stone suddenly “becomes” singular, capturing all my attention. I examine its conglomerated shape, the striking combination of colors in its materials, and I trace its contours with my fingers—contours revealed by the erosion of time. I also carefully assess its weight, because I rarely pick up just one. When the urge to bring them to the studio takes hold, I might carry up to 20 rocks of various sizes and shapes. I walk with them to the car; sometimes they go into a backpack or a shopping cart, but more often I carry them in the woven cradle formed by my two interlaced hands. Perhaps, later, I’ll decide to paint one.

List of the representational strategies I usually work with:

I have used the trompe-l’œil technique to depict scientific mineral collections through a quick yet precise painterly gesture, focusing on the interplay of color.

I have explored their volume using grayscale gradients that evoke digital rendering processes and the vast scale of geological time.

My most recent strategy has involved drawing the literal perimeter of each stone, in order to enclose human gestures and our compulsion to create patterns.